Guest blog by Phil Lambert

For many soil scientists, the history of human interaction with soil begins around 10,000 years ago, when early humans started farming. However, before the agricultural revolution, there was a cultural revolution, and soil played a key part in this too.

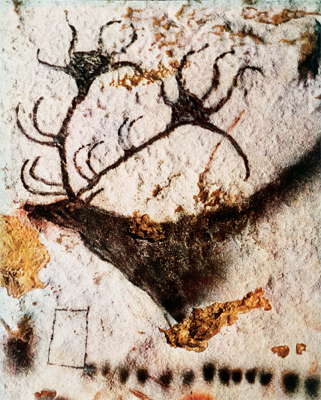

Lascaux Cave – grotte Lascaux – photo Public Domain

The earliest cave paintings, from 40,000 years ago, were created with natural pigments like ochre, sourced from iron-rich soils. These paintings, found in places like Lascaux, often depict animals, handprints, and symbols, believed to represent hunting and spiritual beliefs. Recognising different soils and their associated fauna would have been crucial to early Humans, and surely a key part of their indigenous culture. The pigment itself, or soil, likely also carried significant meaning, beyond its visual use.

Over 100,000 years ago, Neanderthals engaged with soil in meaningful ways too, using ground pigments and polishing rocks and shells for jewellery. Today, soil remains an integral part of human culture. Many tribal societies continue to use soil for sun protection, pest control, and in rituals. And before you think contemporary life has distanced us from these practices, consider this: soils and clays are key ingredients in many contemporary makeup brands.

Soil as pigment has a long tradition. Renaissance artists often used colours like Yellow Ochre, Burnt Sienna, and Raw Umber, which are still in use today. However, these pigments are now typically synthesised from iron oxides rather than sourced directly from soils. This shift severs our connection to both the past and the natural world. These fine, synthetic pigments now blur with toxic Lead and Cadmium pigments, produced in unknown factories and shipped worldwide with uncertain environmental and health implications.

For many contemporary artists, aligning their practice with growing ecological awareness has made the focus on ‘materiality’ and the histories of materials increasingly important.

Coed soil and Silver Nitrate on Rice paper. Photo: Phil Lambert

Fast forward to Cardiff in December 2024, where I found myself gathering with Britain’s leading soil scientists at the British Society of Soil Science’s annual conference. Along with a handful of other artists, I was there to demonstrate creative ways of engaging with soil.

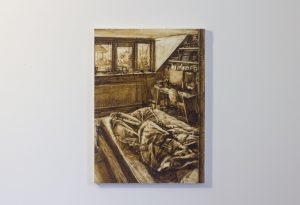

- Isla’s bedroom 2023 soil in oil on paper 52x73cm mounted. Photo: Phil Lambert

- Hope 2023 Soil in linseed oil on paper 240x340mm mounted 2. Photo: Phil Lambert

I’ve been making my own ‘Wild Pigments’ for over five years. Through working with a single pigment, like soil from my garden, I focus on the materiality and process of painting, while also exploring the metaphors and cultural associations tied to soil. Using soil not only raises awareness of our environmental impact, but also allows me to delve into themes like mortality, creativity, growth and connection to place. My painting work blends observational techniques, landscape traditions, abstraction, and influences from science, philosophy, as well as my family life and work in social care research.

My representational works vary from depictions of weeds and turf to scenes of domestic life, encouraging reflection on routines like cleaning and cooking, alongside themes of community and place and within a practise of observation (becoming more aware).

My representational works vary from depictions of weeds and turf to scenes of domestic life, encouraging reflection on routines like cleaning and cooking, alongside themes of community and place and within a practise of observation (becoming more aware).

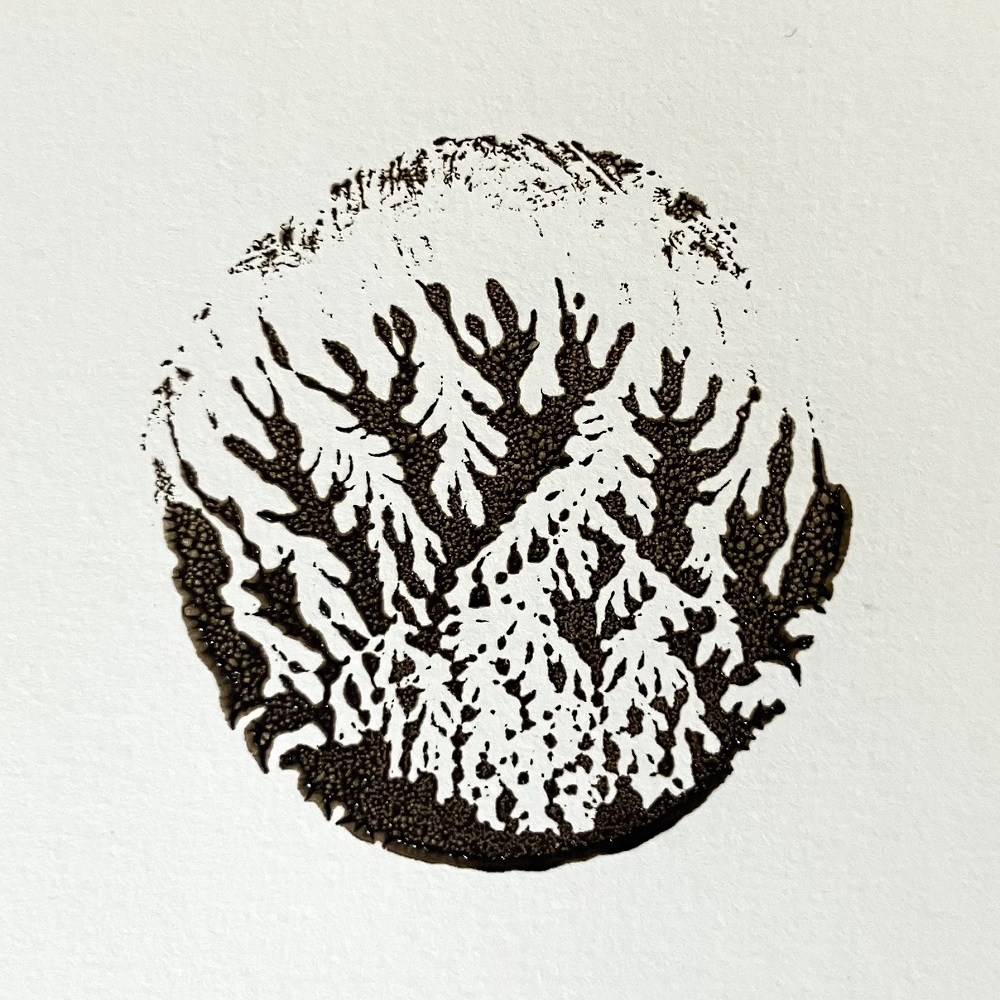

Abstract pieces, which emerge unplanned from the geometry within the rectangle, reference the foundational role soil plays in human societies. While the banner image is a variation of the Pfeiffer CC test I’ve been experimenting with. This old soil assaying technique, with dubious scientific value, traces its influence to Rudolf Steiner, the Austrian polymath who blurred the boundaries between science, spirituality, and art at the turn of the 19th century.

At the conference, I also demonstrated paint-making, encouraging delegates to create their own soil-based watercolours and unique ‘Muller’ stamps. This tactile experience offered a refreshing contrast to the more cerebral talks on science and policy. No one could resist interpreting the Muller stamps, seeing patterns like corals, plants, and brains.

Perhaps, in homage to Steiner and our ancient ancestors, this activity reconnects us to the spiritual realm of soil – but above all, it’s just fun.

A reminder to us all that, at heart, we all share an ancestral love of playing with dirt.

Muller stamp, Photo: Phil Lambert

Website: www.phillambert.co.uk

Social media: pwrlambert